The geometrical viewpoint

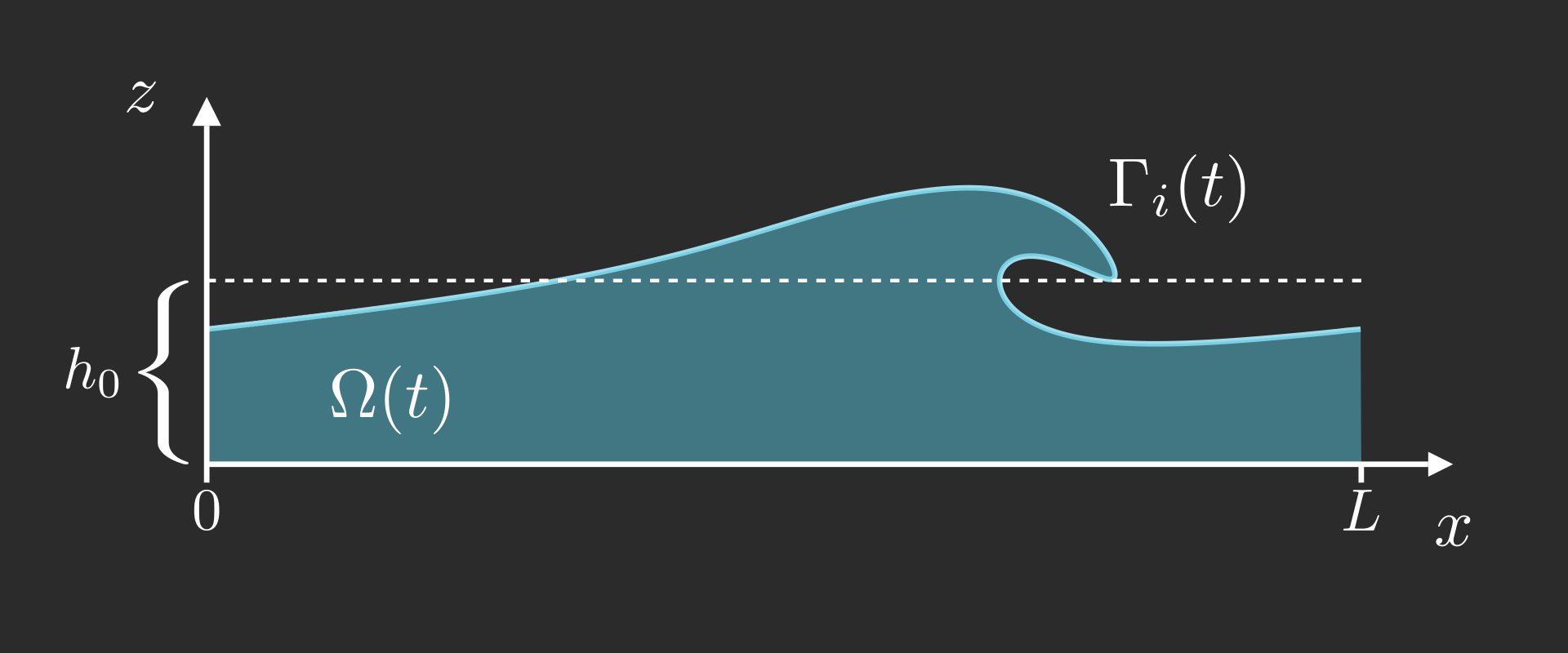

- To compute the shape of the wave

- Explicit interface representation

- Lagrangian advection

- Fails as the splash singularity occurs

The phenomenological viewpoint

- To compute the energy dissipation

- Implicit interface representation

- Eulerian advection

- Mostly two-fluids studies

Superharmonic Instability

Longuet-Higgins (1978)

Longuet-Higgins & Cokelet (1978)

⤷ using the numerical method of Longuet-Higgins & Cokelet (1976)

Later confirmed and extended by:

Tanaka (1983, 1985)

Tanaka, Dold, Lewy & Peregrine (1987)

Irrotationality and water waves:

\[\omega = \boldsymbol{\nabla}\times\boldsymbol{u} = 0\]

- A theoretical framework for irrotational breaking waves

- An extension of the Zakharov-Craig-Sulem formulation for parametrised surfaces

- Hamiltonian structure and the link with the Water Waves equations

- Did you just say "irrotational"?

- Numerical method for the Navier-Stokes system

- When are water waves really irrotational?

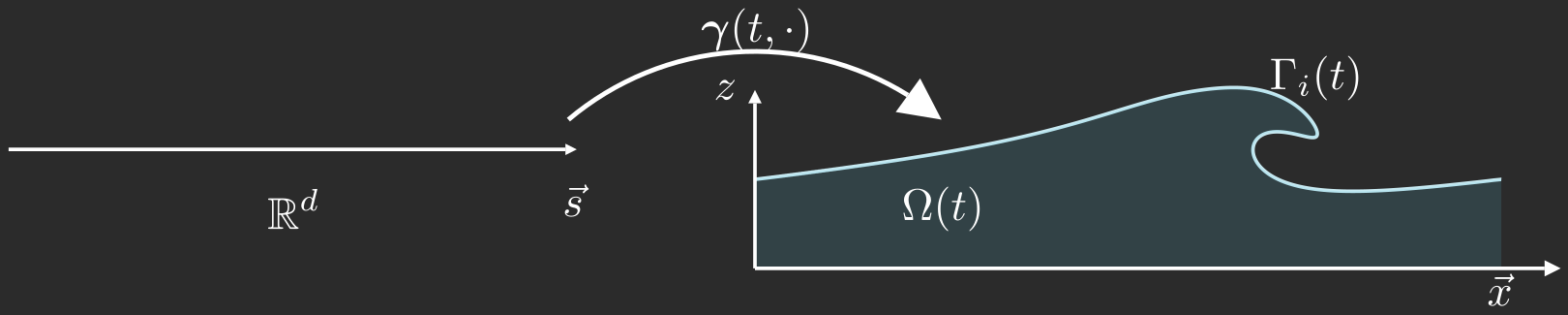

Let \(d = 1\) or \(d=2\) the intrinsic dimension of the free surface

Scalar quantities: \(a,b,c,\cdots\)

\(d-\)dimensional quantities: \(\vec{a},\vec{b},\vec{c},\cdots\)

\((d+1)-\)dimensional quantities: \(\boldsymbol{a},\boldsymbol{b},\boldsymbol{c},\cdots\)

In Craig (2017), the 2D irrotational Euler equation is rephrased as a 1D equation (\(d=1\)) using quantities defined only on the free surface.

What we would like to do:

- Investigate the Hamiltonian structure

- Find a link with the Water Waves equations of Zakharov (1968)Craig & Sulem (1993)

- Find a formulation with \(d=2\)

Other formulations encompassing wave breaking:

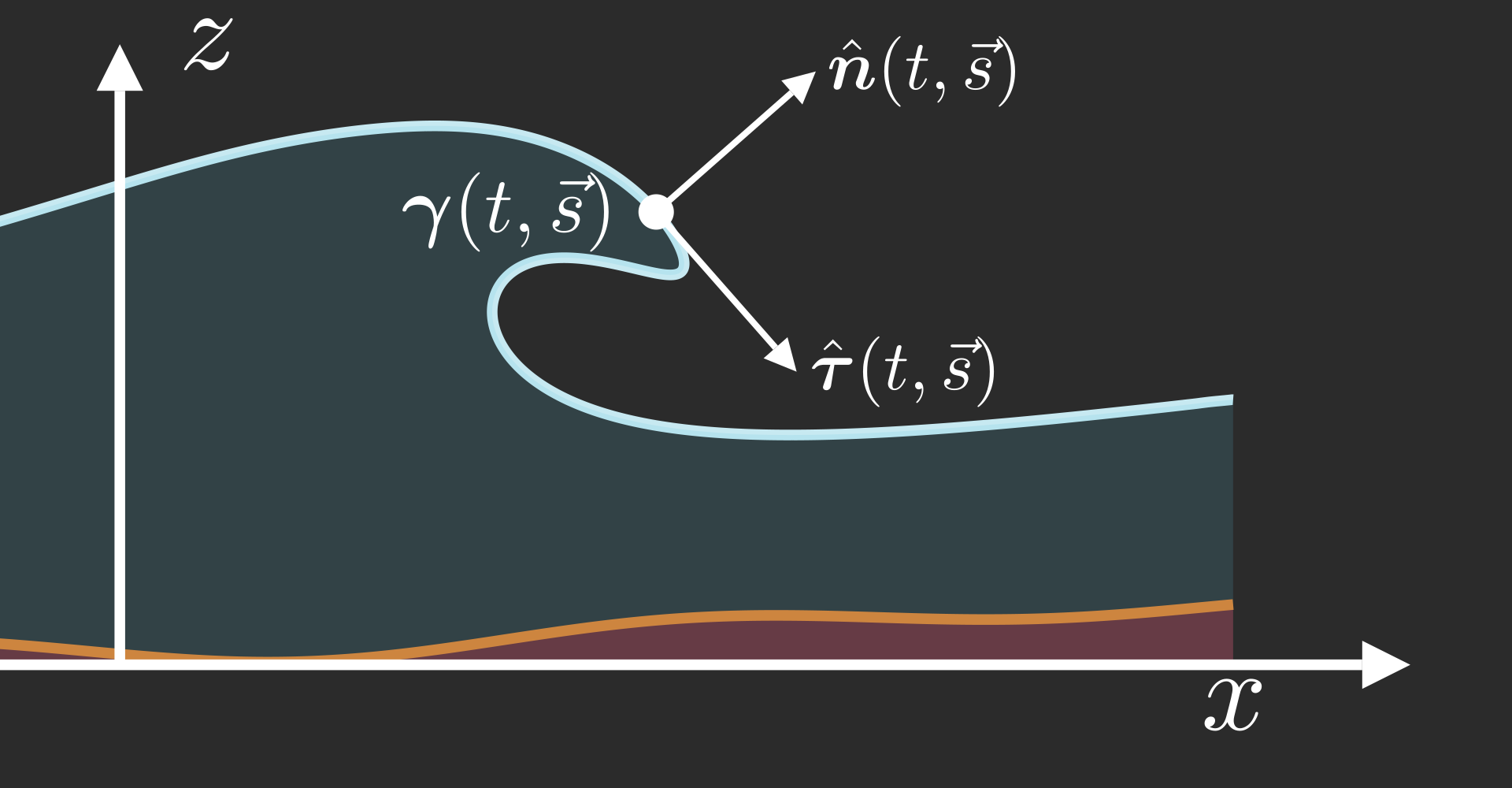

The interface is a parametrised \(d-\)dimensional surface

\[ \Gamma_i(t) = \bigcup_{\vec{s}\in\mathbb{R}^d} \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) \]

Each interface point is advected with the fluid's velocity \(\boldsymbol{u}\)

\[ \partial_t \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) = \boldsymbol{u}\big(t, \boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) \big) \]

Only the normal velocity actually changes the shape of the free surface

\[ \partial_t \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) = u_n\big(t,\boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) \big) \hat{\boldsymbol{n}}(t,\vec{s})\qquad\text{with}\qquad u_n = \boldsymbol{u} \cdot \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} \]

We can even choose an arbitrary velocity (fittingly)

\[ \partial_t \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) = u_n\big(t,\boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) \big) \hat{\boldsymbol{n}}(t,\vec{s}) + \boldsymbol{v}(t,\vec{s})\qquad\text{with}\qquad \boldsymbol{v}(t,\vec{s}) \in \mathrm{T}_{\boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s})}\Gamma_i(t) \]

The interface is the zero level set of a function

\[ \Gamma_i(t) = \big(F(t,\cdot)\big)^{-1} \big(\{0\}\big) \]

The advection is achieved in a Eulerian manner

\[ \partial_t F + \boldsymbol{u} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} F = 0 \]

The original "crime" of Saint-Venant (1871): assuming that \(F\) has the following shape, \[ F(t,\boldsymbol{x}) = z - h(t,\vec{x}) \] i.e. that no breaking happens.

Consequently, \[ \partial_t h = u_z - \vec{u} \cdot \vec{\nabla} h = \boldsymbol{u}\cdot \boldsymbol{n}\qquad\text{with}\qquad \boldsymbol{n} = \begin{bmatrix} - \vec{\nabla}h \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \]

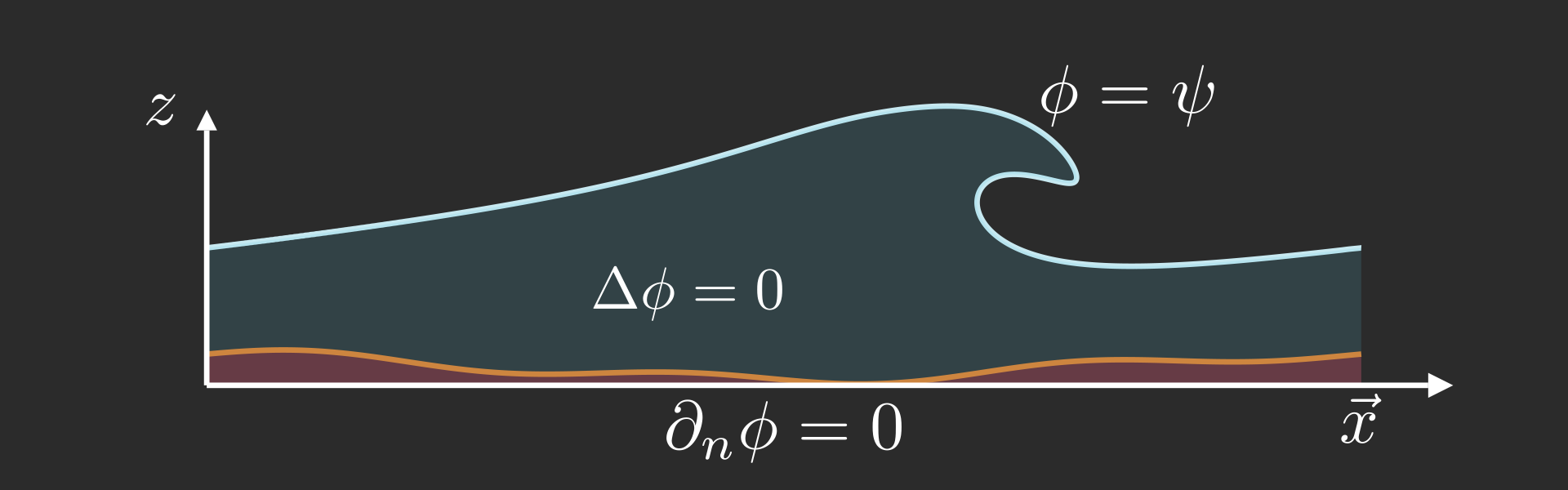

We now assume that \(\boldsymbol{\omega} = \boldsymbol{\nabla}\times \boldsymbol{u} = 0\)

Hence, \( \boldsymbol{u} = \boldsymbol{\nabla} \phi \) for some potential \(\phi\)

Introduce the free-surface potential \(\psi\) \[ \psi(t,\vec{s}) = \phi\big( t, \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) \big) \]

Euler's system, \[\begin{align} \partial_t \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{u}\cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u} &= - \boldsymbol{\nabla} p + \boldsymbol{g} \\ \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u} &= 0 \end{align}\] Assuming irrotationality, we obtain (Daniel) Bernoulli's law in the Eulerian frame, \[\partial_t \phi \style{color: #42affa;}{+} \frac{1}{2}\, \big| \boldsymbol{\nabla} \phi \big|^2 + p + g z = 0 \] On the free surface, this becomes \[\partial_t \phi \big|^2\Big|_{\boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s})} + \frac{1}{2}\, \big| \boldsymbol{\nabla} \phi \big|^2\Big|_{\boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s})} + g \gamma_z = 0 \]

\[ \mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi = \boldsymbol{u}\cdot\boldsymbol{n} = \boldsymbol{n}\cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla}\phi \]

In general, the normalisation is related to the determinant of the metric \(\mathsf{g}(t,\vec{s})\), \[\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi(t,\vec{s})= \sqrt{\det(\mathsf{g})}\ \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla}\phi\big( t, \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) \big)\]

\(d = 1\)

\[ \mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi(t,\vec{s})= \big|\partial_s\boldsymbol{\gamma}\big|\ \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla}\phi\big( t, \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) \big) \]

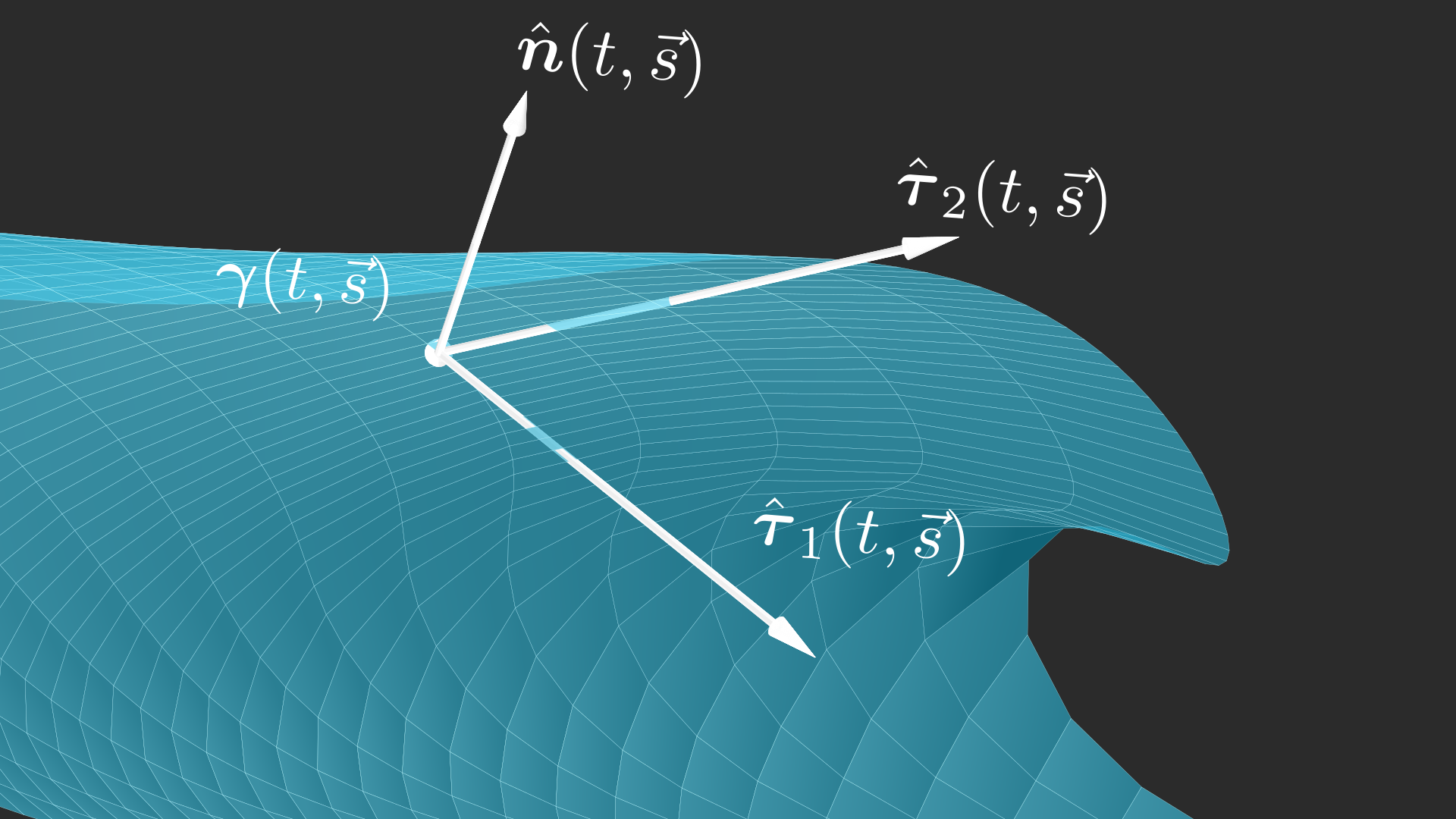

\(d = 2\)

\[ \mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi(t,\vec{s})= \big|\partial_{s_1}\boldsymbol{\gamma} \times \partial_{s_2}\boldsymbol{\gamma}\big|\ \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla}\phi\big( t, \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s}) \big) \]

Explicit representation

\[\psi(t,\vec{s}) = \phi\big|_{\boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s})}\] \(\psi\) is a function of the curved-space variable \(\vec{s}\), and \[\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi(t,\vec{s}) = \boldsymbol{n}(t,\vec{s})\cdot\boldsymbol{\nabla}\phi\big|_{\boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\vec{s})}\]

Implicit representation

\[\Psi(t,\vec{x}) = \phi\big|_{z = h(t,\vec{x})}\] \(\Psi\) is a function of the flat-space variable \(\vec{x}\), then \[\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\Psi(t,\vec{x}) = \boldsymbol{n}(t,\vec{x})\cdot\boldsymbol{\nabla}\phi\big|_{z = h(t,\vec{x})}\]

With an arbitrary tangential velocity \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rcl} \partial_t \boldsymbol{\gamma} &=& \cfrac{\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|} \,\hat{\boldsymbol{n}} + v \hat{\boldsymbol{\tau}}\\ \partial_t \psi &=& -g \gamma_z + \cfrac{1}{2} \left( \cfrac{\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|} \right)^2 + \cfrac{\partial_s\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|} \left[ v - \cfrac{1}{2}\cfrac{\partial_s\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|} \right] \end{array} \right. \]

With a purely Lagrangian tangential velocity \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rcl} \partial_t \boldsymbol{\gamma} &=& \cfrac{\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|} \,\hat{\boldsymbol{n}} + \cfrac{\partial_s\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|}\, \hat{\boldsymbol{\tau}}\\ \partial_t \psi &=& -g \gamma_z + \cfrac{1}{2} \left( \cfrac{\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|} \right)^2 \style{color: #42affa;}{+} \cfrac{1}{2} \left(\cfrac{\partial_s\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|}\right)^2 \end{array} \right. \]

Without tangential velocity \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rcl} \partial_t \boldsymbol{\gamma} &=& \cfrac{\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|} \,\hat{\boldsymbol{n}}\\ \partial_t \psi &=& -g \gamma_z + \cfrac{1}{2} \left( \cfrac{\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|} \right)^2 \style{color: #42affa;}{-} \cfrac{1}{2} \left(\cfrac{\partial_s\psi}{|\partial_s \boldsymbol{\gamma}|}\right)^2 \end{array} \right. \]

Lemma (Longuet-Higgins, 1953)

Assume that \(\boldsymbol{\gamma}(t=0,\cdot)\) corresponds to the arclength parametrisation of \(\Gamma_i(0)\) and that the tangential velocity \(v\) is chosen such that \[ \partial_s v = \kappa u_n, \] with \(\kappa\) the curvature. Then \(\boldsymbol{\gamma}(t,\cdot)\) corresponds to the arclength parametrisation of \(\Gamma_i(t)\).

Tangent vectors: \[\hat{\boldsymbol{\tau}}_i = \frac{\partial_{s_i} \boldsymbol{\gamma}}{|\partial_{s_i} \boldsymbol{\gamma}|}\] Intrinsic metric tensor: \[\mathsf{g}_{ij} = \begin{bmatrix} \partial_{s_i} \boldsymbol{\gamma} \cdot \partial_{s_j} \boldsymbol{\gamma} \end{bmatrix}\]

\[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rcl} \partial_t \boldsymbol{\gamma} &=& \cfrac{\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi}{\sqrt{\det \mathsf{g}}} \,\hat{\boldsymbol{n}} + \begin{bmatrix} \partial_{s_1} \psi & \partial_{s_2} \psi \end{bmatrix} \mathsf{g}^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} \partial_{s_1} \boldsymbol{\gamma} \\ \partial_{s_2} \boldsymbol{\gamma} \end{bmatrix} \\ \partial_t \psi &=& -g \gamma_z + \cfrac{1}{2} \cfrac{\big(\mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi\big)^2}{\det \mathsf{g}}\style{color: #42affa;}{+} \begin{bmatrix} \partial_{s_1} \psi & \partial_{s_2} \psi \end{bmatrix} \mathsf{g}^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} \partial_{s_1} \psi \\ \partial_{s_2} \psi \end{bmatrix} \end{array} \right. \]

The system of Zakharov (1968)Craig & Sulem (1993) \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rcl} \partial_t h &=& \mathrm{DtN}[h]\Psi \\ \partial_t \Psi &=& -g h - \cfrac{1}{2} \big|\vec{\nabla}\Psi\big|^2 + \cfrac{1}{2} \cfrac{\big( \mathrm{DtN}[h]\Psi + \vec{\nabla}\Psi \cdot \vec{\nabla} h \big)^2}{1 + |\vec{\nabla} h|^2} \end{array} \right. \]

Defining the following Hamiltonian functional, \[ \mathrm{H}[h,\Psi] = \frac{1}{2} \int_{\mathbb{R}^d} \Psi\ \mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\Psi + \frac{g}{2} \int_{\mathbb{R}^d} h^2 \] the Water Waves equations can be recast as \[ \partial_t \begin{bmatrix} h \\ \Psi \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ -1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \delta_h \mathrm{H} \\ \delta_\Psi \mathrm{H} \end{bmatrix} \]

Define the following Hamiltonian functional

\[ \mathrm{H}[\boldsymbol{\gamma},\psi] = \frac{1}{2} \int_{\mathbb{R}^d} \psi\ \mathrm{DtN}[\boldsymbol{\gamma}]\psi + \frac{g}{2} \int_{\mathbb{R}^d} \big(\gamma_z\big)^2\, \hat{\boldsymbol{z}} \cdot \hat{\boldsymbol{n}}\, \sqrt{\det \mathsf{g}} \]

then, we can show (when \(d=1\) or \(2\)) that \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rccccl} \partial_t \boldsymbol{\gamma} &=& & \cfrac{\boldsymbol{n}}{\det \mathsf{g}} && \cfrac{\delta \mathrm{H}}{\delta \psi} + \text{tangential terms} \\ \partial_t \psi &=& -& \cfrac{\boldsymbol{n}}{\det \mathsf{g}} & \cdot & \cfrac{\delta \mathrm{H}}{\delta \boldsymbol{\gamma}} + \text{tangential terms} \end{array} \right. \] This is in fact a Hamiltonian system with non-canonical symplectic structure (following the definitions ofBenjamin & Olver (1982) or Kuksin (2000)).

Definition

A solution \( (\boldsymbol{\gamma},\psi) \) of the Breaking Waves equations (!) is said to have broken at time \(t \geq 0\) if \( \partial_s\gamma_x(t,\cdot) \) fails to be invertible at some point.

At a time \(t \geq 0\), if the wave (i.e. the solution) has not broken, we can define the two following quantities unambiguously \[ h(t,x) = \gamma_z\big(t,X_t^{-1}(x)\big)\qquad\text{and}\qquad\Psi(t,x) = \psi\big(t,X_t^{-1}(x)\big) \]

Proposition

At a time \(t \geq 0\), if the solution to the BW eqs. has not broken, then the couple \((h,\Psi)\) is a (formal) solution of the Water Waves equations.

Irrotationality and in water waves:

\[\omega = \boldsymbol{\nabla}\times\boldsymbol{u} = 0\]

- A theoretical framework for irrotational breaking waves

- An extension of the Zakharov-Craig-Sulem formulation for parametrised surfaces

- Hamiltonian structure and the link with the Water Waves equations

- Did you just say "irrotational"?

- Numerical method for the Navier-Stokes system

- When are water waves really irrotational?

Euler (+ irrotationality)

-

Mapping to the unit circle in \(\mathbb{C}\):

⤷Longuet-Higgins & Cokelet (1976) -

The vortex and dipole methods:

⤷Baker, Meiron & Orszag (1982)

⤷Baker & Xie (2011)

⤷Dormy & Lacave (2024) -

Boundary Element Methods (BEM) in 3D:

⤷Grilli, Guyenne & Dias (2001)

Navier-Stokes

-

Two-dimensional studies:

⤷Chen, Kharif, Zaleski & Li (1999) -

Three-dimensional studies:

⤷Lubin & Glockner (2015)

⤷Deike, Popinet & Melville (2015)

⤷Mostert, Popinet & Deike (2022)

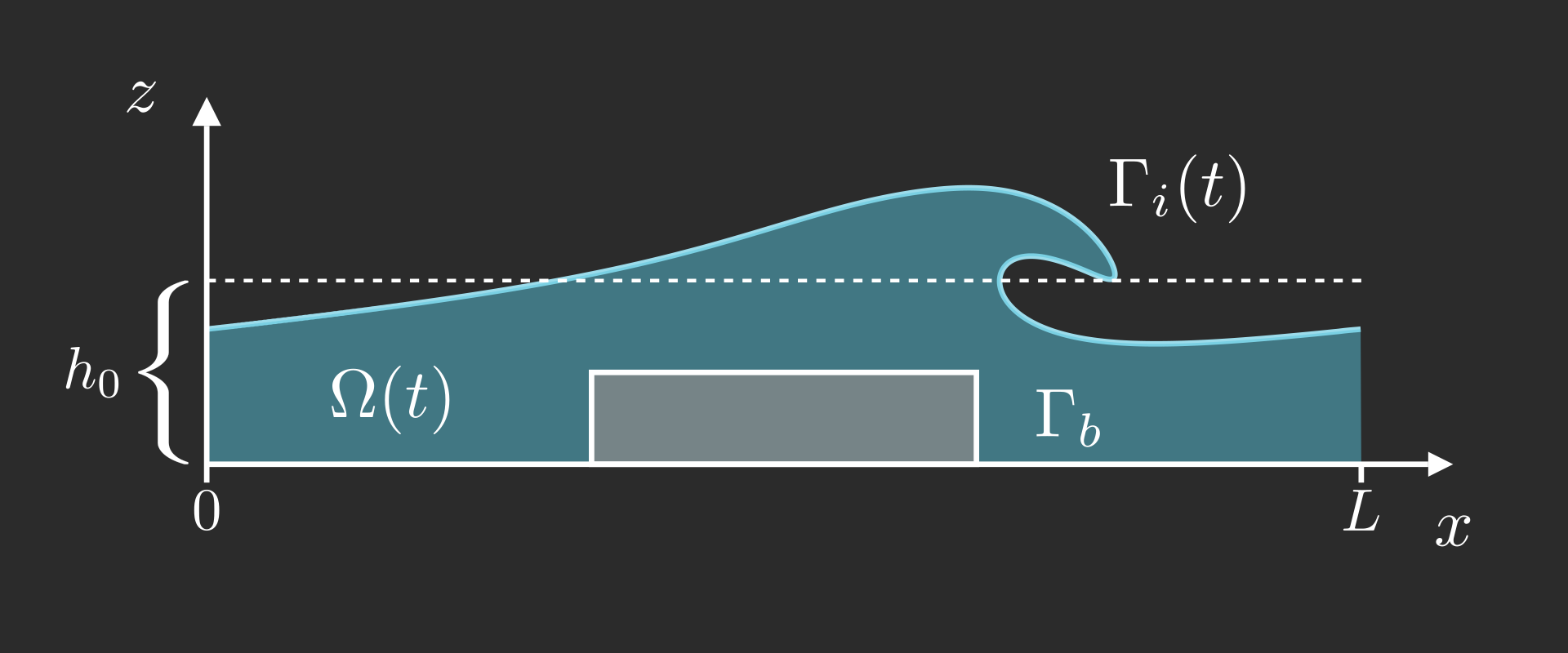

Non-dimensional quantities: \[ \begin{align} \boldsymbol{x} & \to h_0 \boldsymbol{x} \\ \boldsymbol{u} & \to \sqrt{gh_0} \boldsymbol{u} \\ p & \to \rho g h_0 p \\ \end{align} \] yielding the following Reynolds number, \[ \mathrm{Re} = \frac{h_0 \sqrt{gh_0}}{\nu} \]

Incompressible, non-dimensional Navier-Stokes equations in \(\Omega(t)\) \[ \begin{align} \partial_t \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{u} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u} &= - \boldsymbol{\nabla}p + \frac{1}{\mathrm{Re}}\, \Delta \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{g} \\ \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u} &= 0 \end{align} \]

Stress-free boundary condition on the free surface \[ \begin{align} p \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} - \frac{1}{\mathrm{Re}} \, \Big[ \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u} + \big(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u}\big)^{\top} \Big] \, \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} &= 0 && \text{on } \Gamma_i(t) \end{align} \] Navier boundary condition on the bottom topography \(\Gamma_b = \{z = 0\}\) \[ \begin{align} \hat{\boldsymbol{\tau}}\,\Big[\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u} + \big(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u}\big)^{\top}\Big] \, \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} &= 0 & u_z &= 0 \end{align} \]

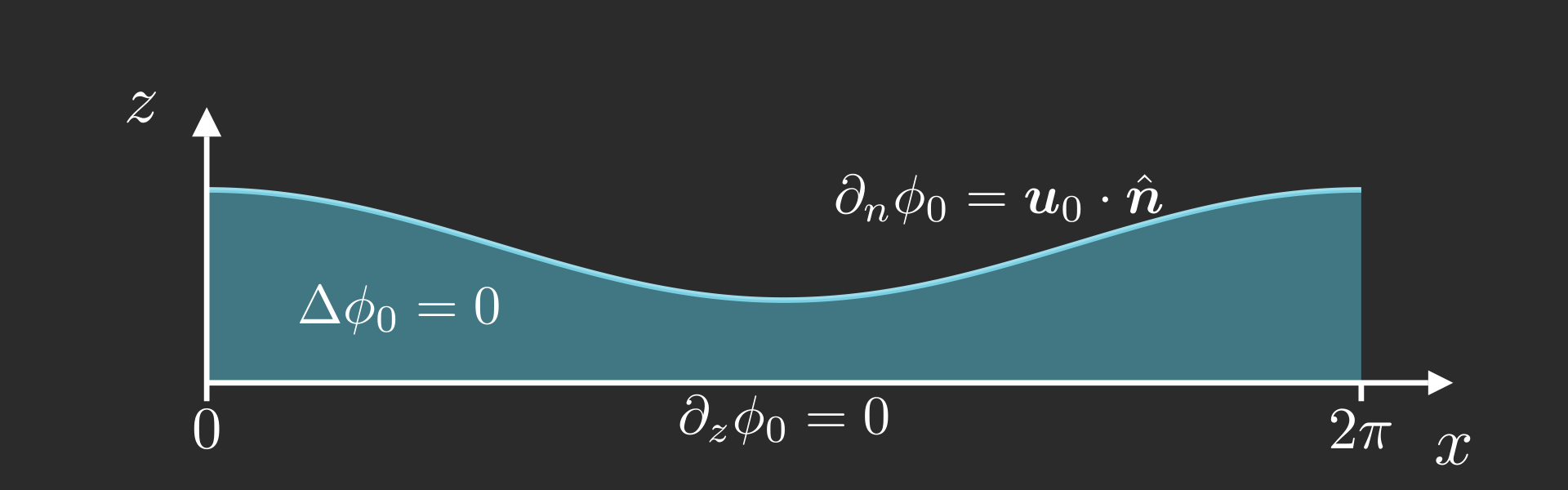

We use the first order (in \(a\)) solution (i.e. a linear wave) of amplitude \(a = 0.5\), \[ \boldsymbol{\gamma}(t=0,s) = \begin{bmatrix} s \\ h_0 + a \cos(kx) \end{bmatrix}\qquad\text{and}\qquad \boldsymbol{u}_0(x,z) = \frac{a\omega}{\sinh(kh_0)} \begin{bmatrix} \cosh(k\style{color: #42affa;}{h_0}) \cos(kx) \\ \sinh(k\style{color: #42affa;}{h_0}) \sin(kx) \end{bmatrix} \] Then we solve numerically the following elliptic problem,

At last, the initial velocity is computed as \( \boldsymbol{u}(t = 0) = \boldsymbol{\nabla} \phi_0 \)

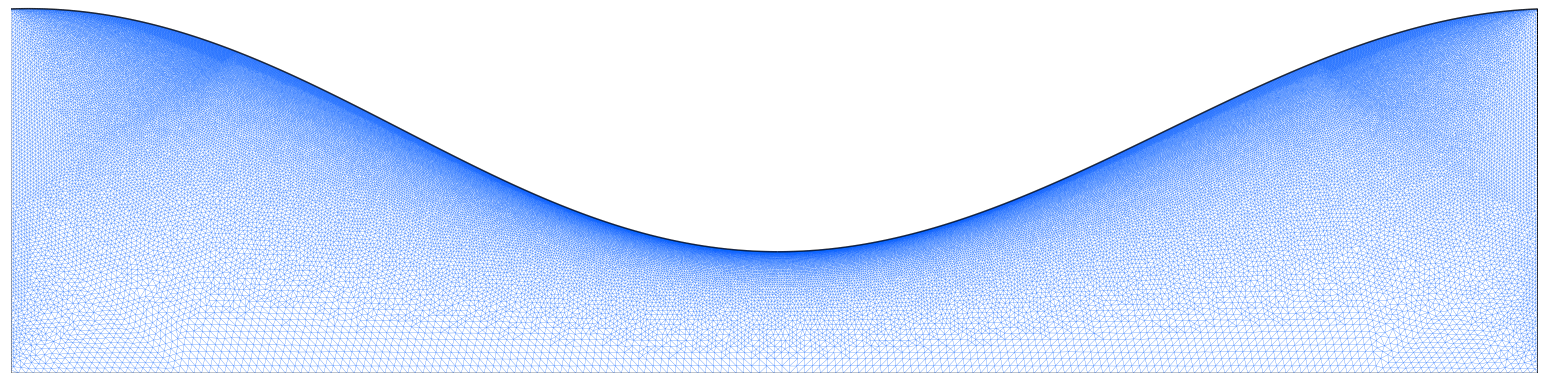

We use the FreeFEM library Hecht (2012) to

- generate and handle the mesh

- build and handle the matrices

- use the PETSc methods easily

Figure - The mesh generated from the initial free surface (\(\approx 200\,000\) triangles).

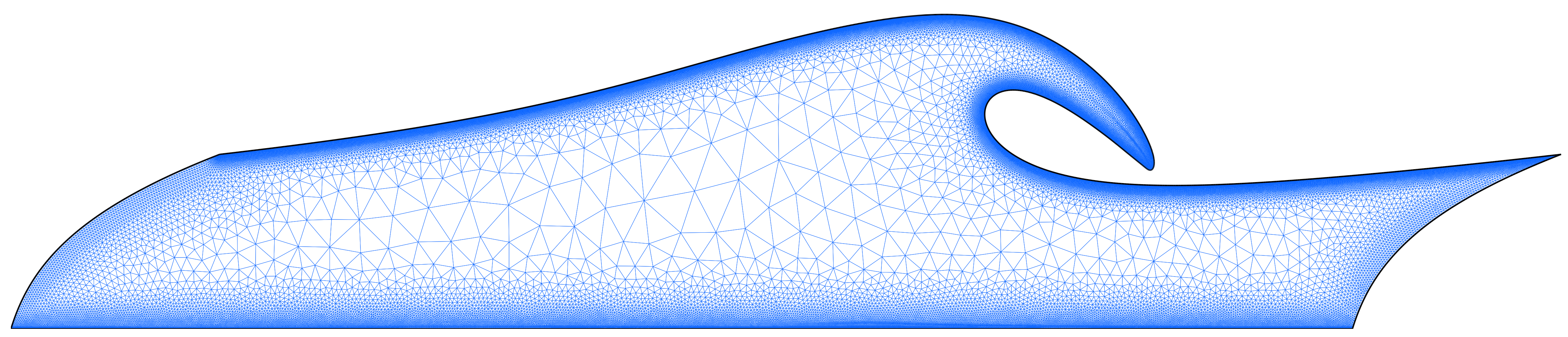

The Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian Method (ALE)

In our case, we compute the mesh's velocity by numerically solving the following elliptic problem at each time step, \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rcll} \Delta \boldsymbol{w} &=& 0 & \text{in the domain } \Omega(t) \\ \boldsymbol{w} &=& \boldsymbol{u} & \text{on the free surface } \Gamma_i(t) \\ \boldsymbol{w} &=& 0 & \text{on the bottom } \Gamma_b \\ \end{array} \right. \]

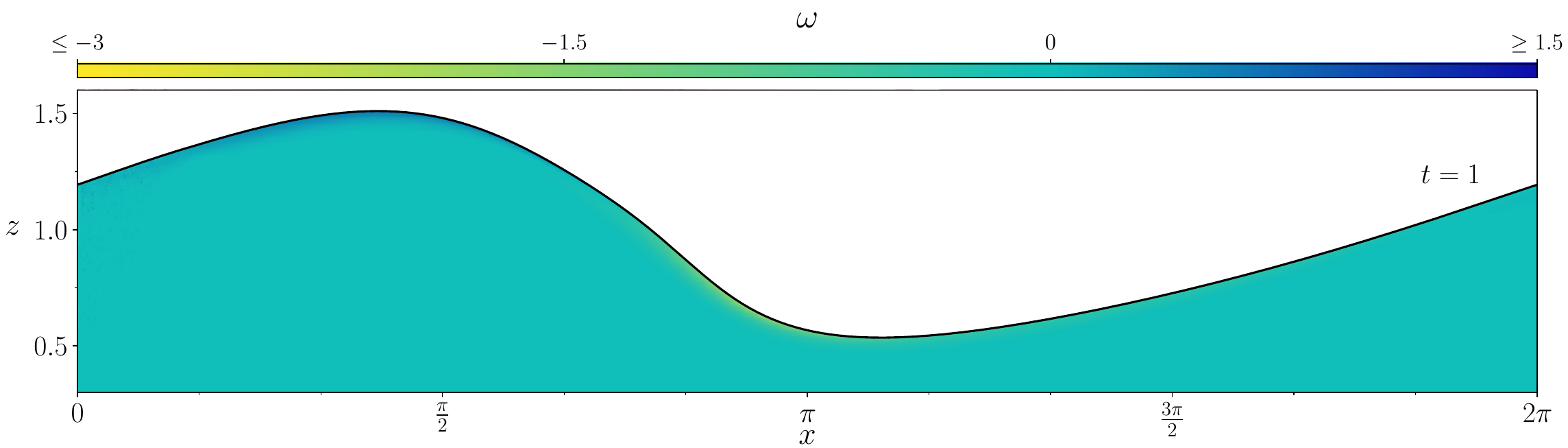

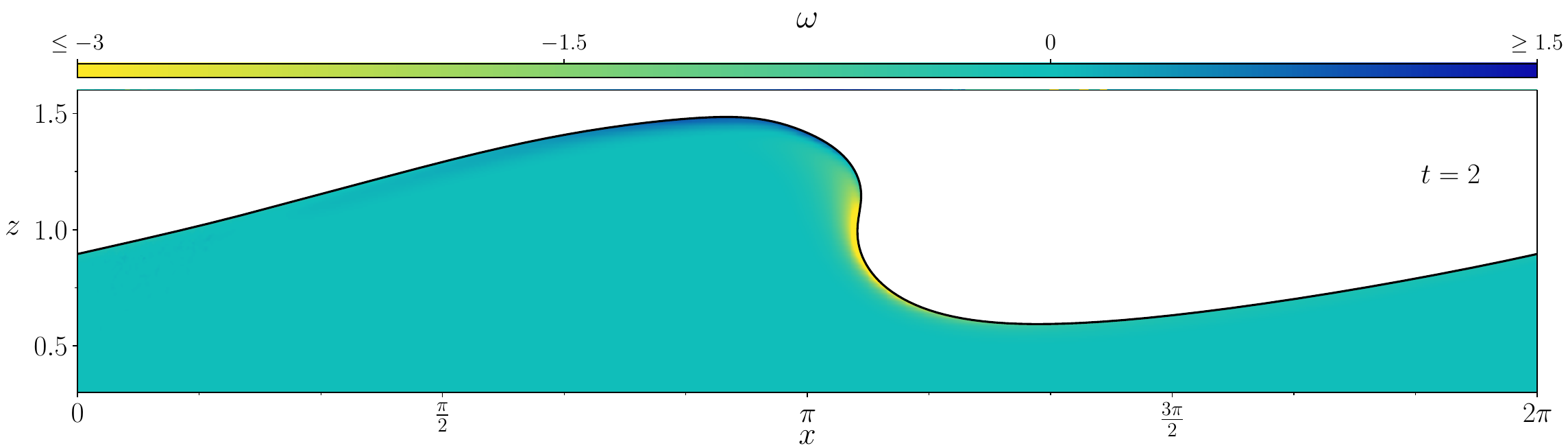

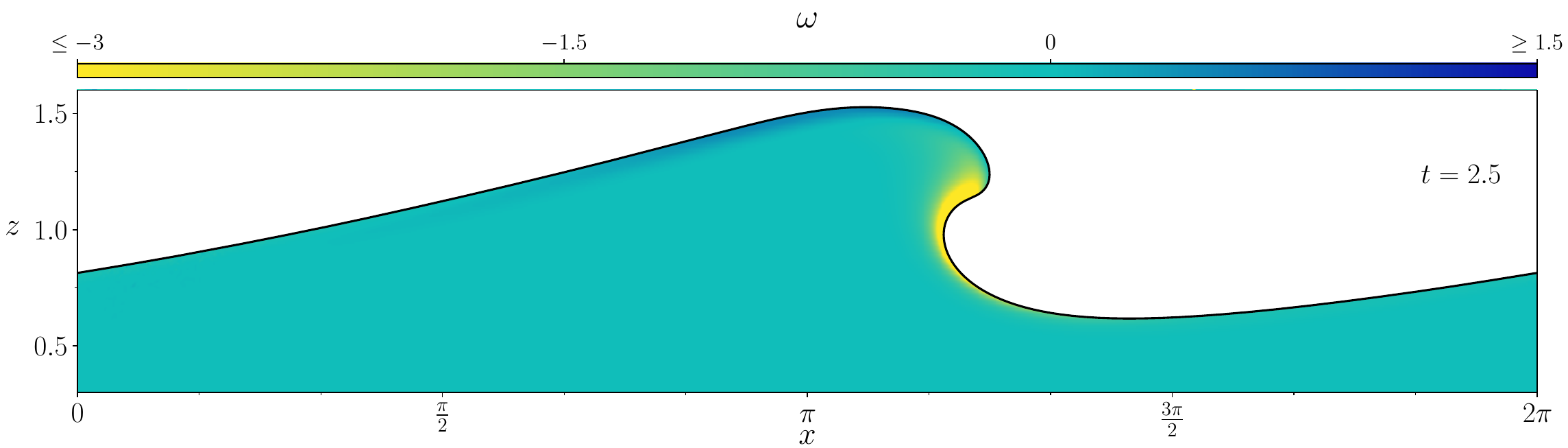

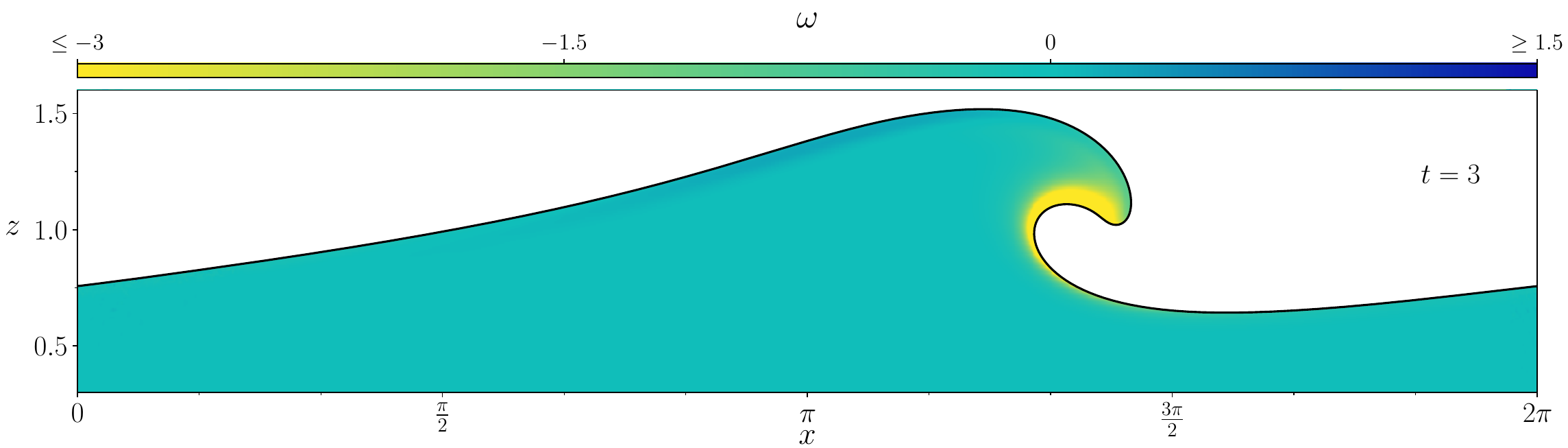

Animated Figure (from R. & Dormy (2024)) - Interface evolution for a Reynolds number \(\mathrm{Re} = 10^6\)

Figure - The mesh close to the end of the simulation shown before.

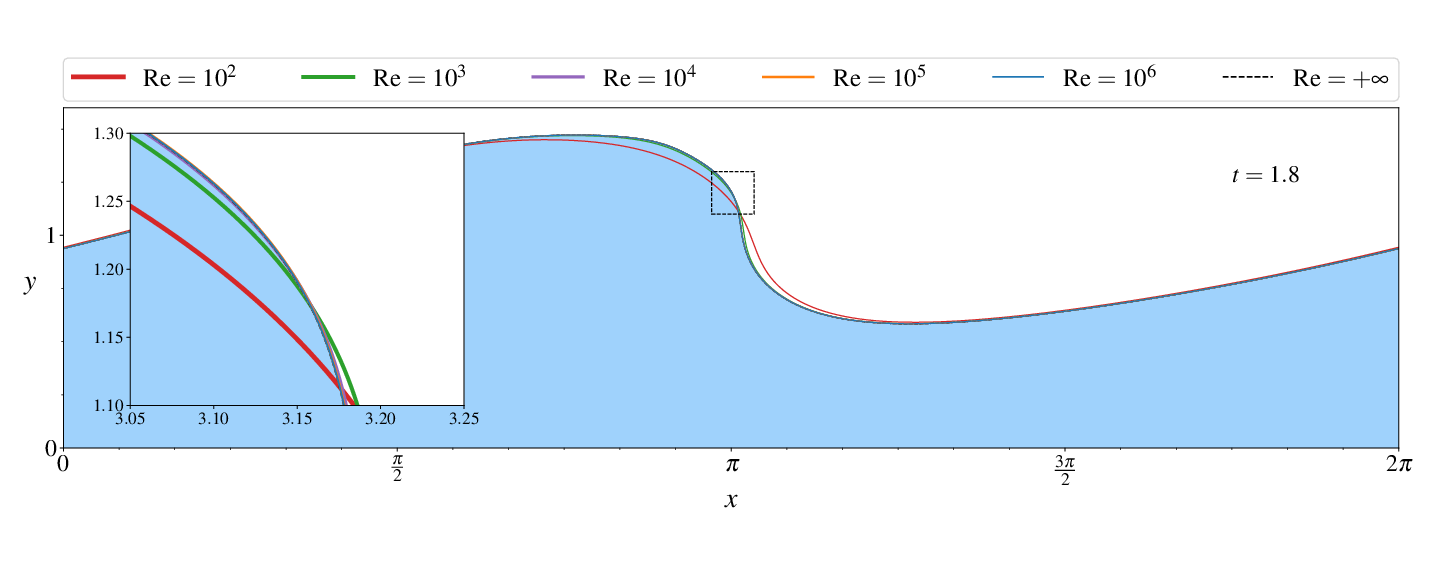

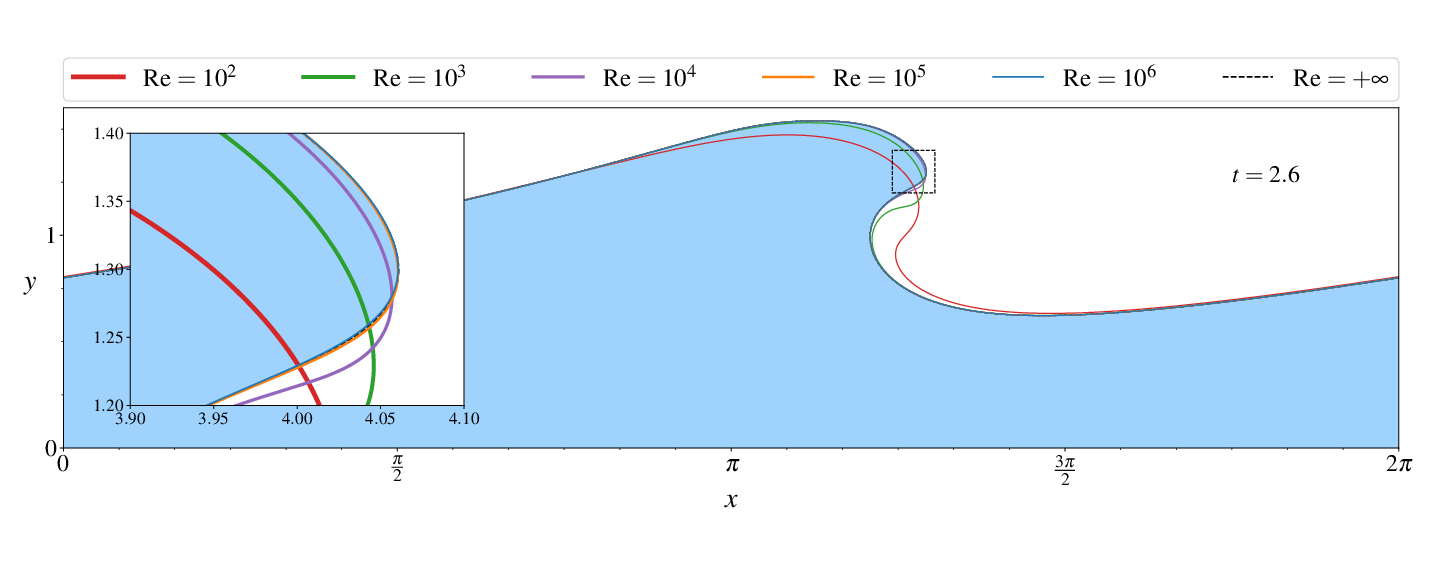

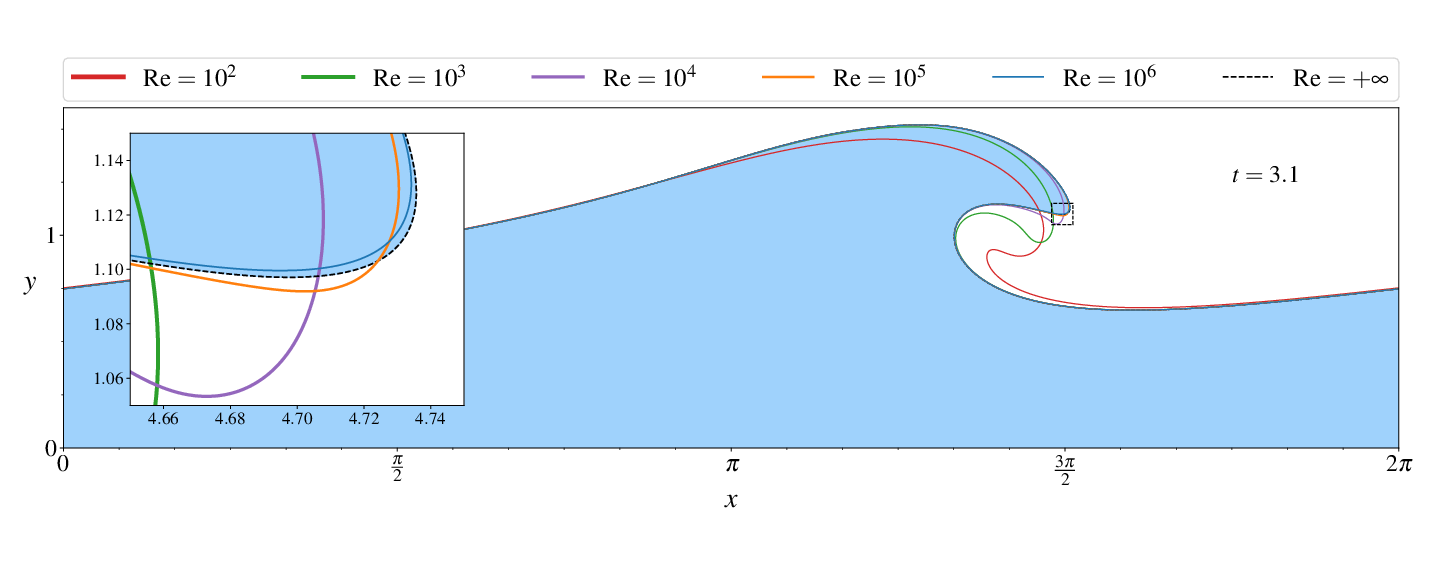

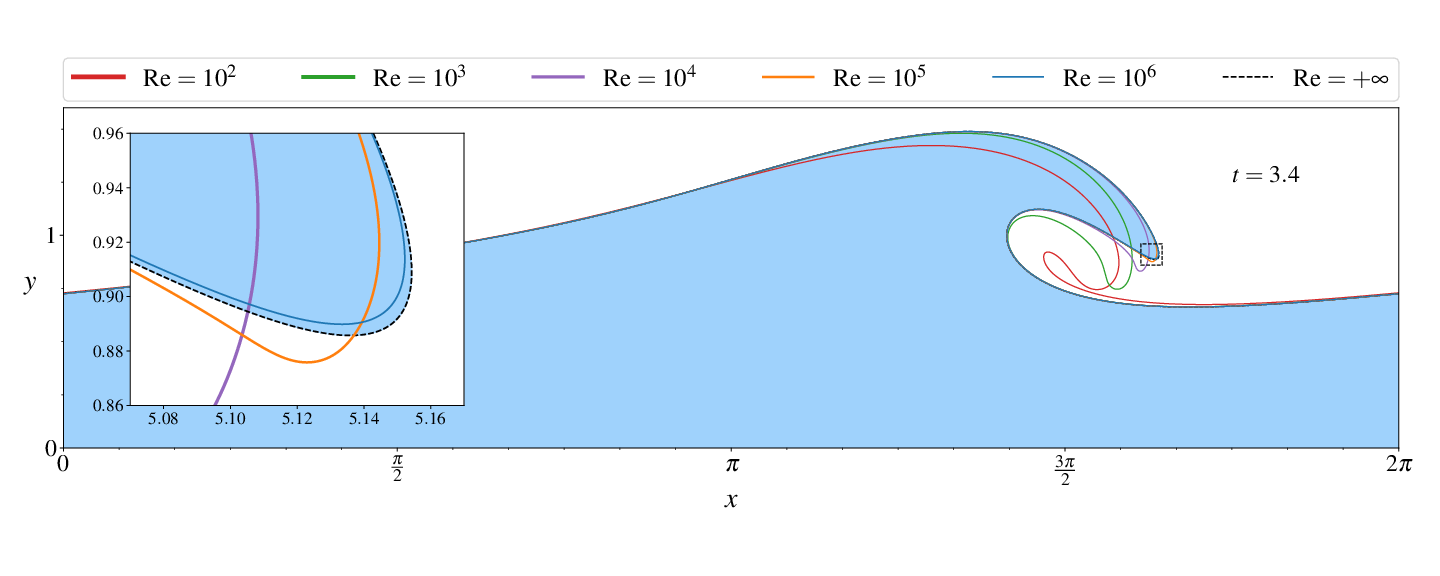

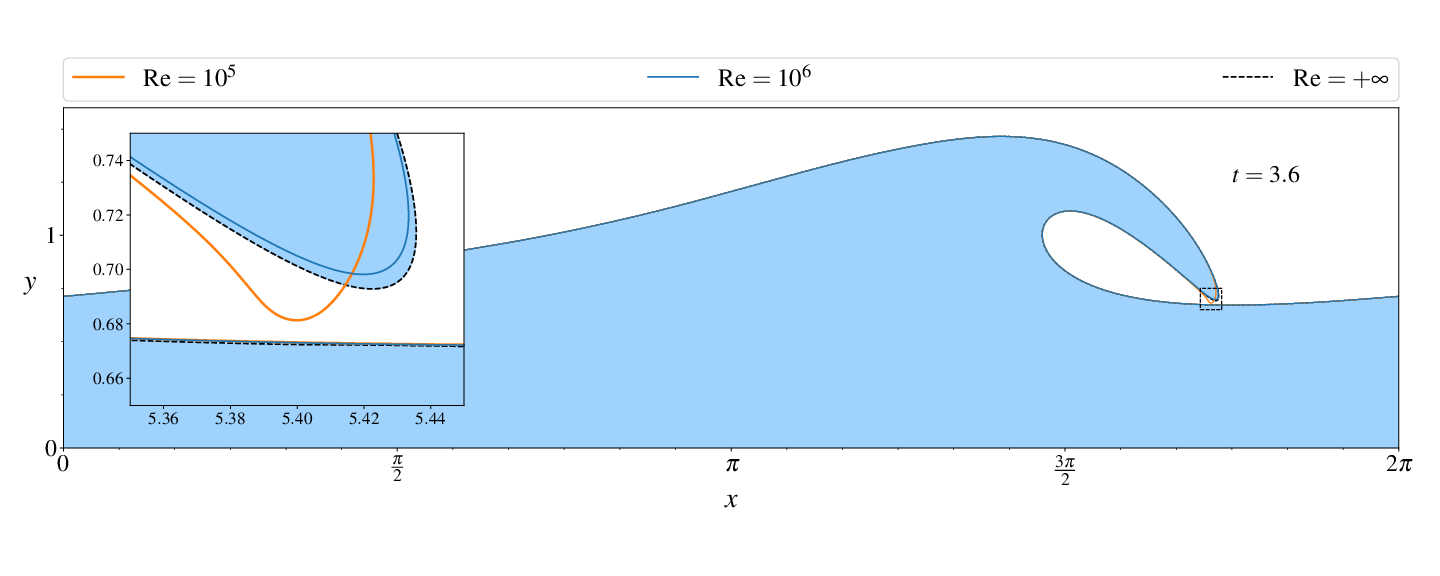

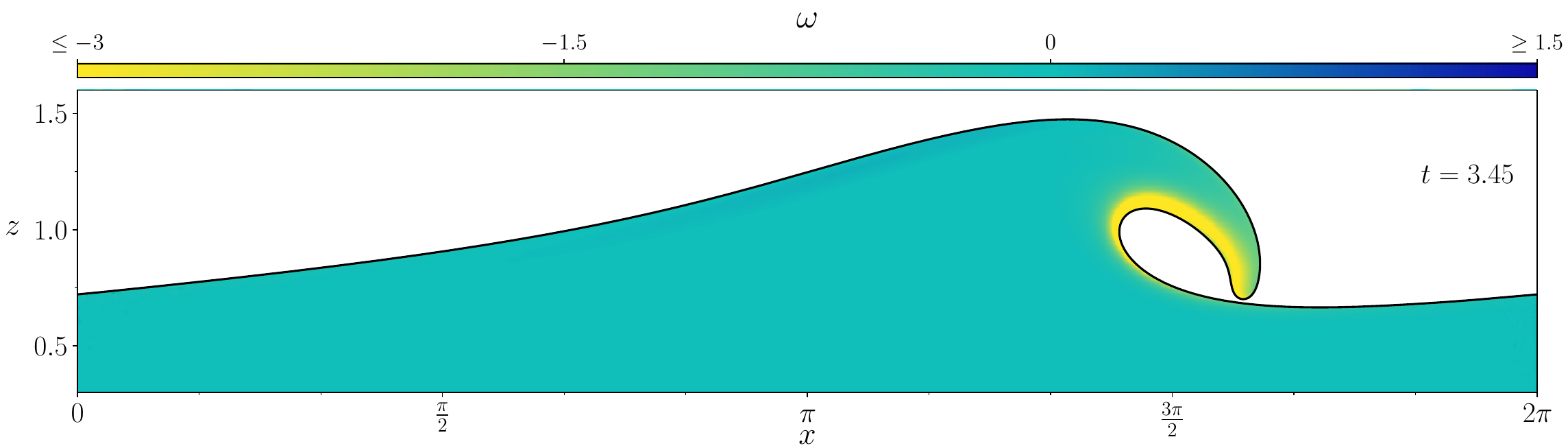

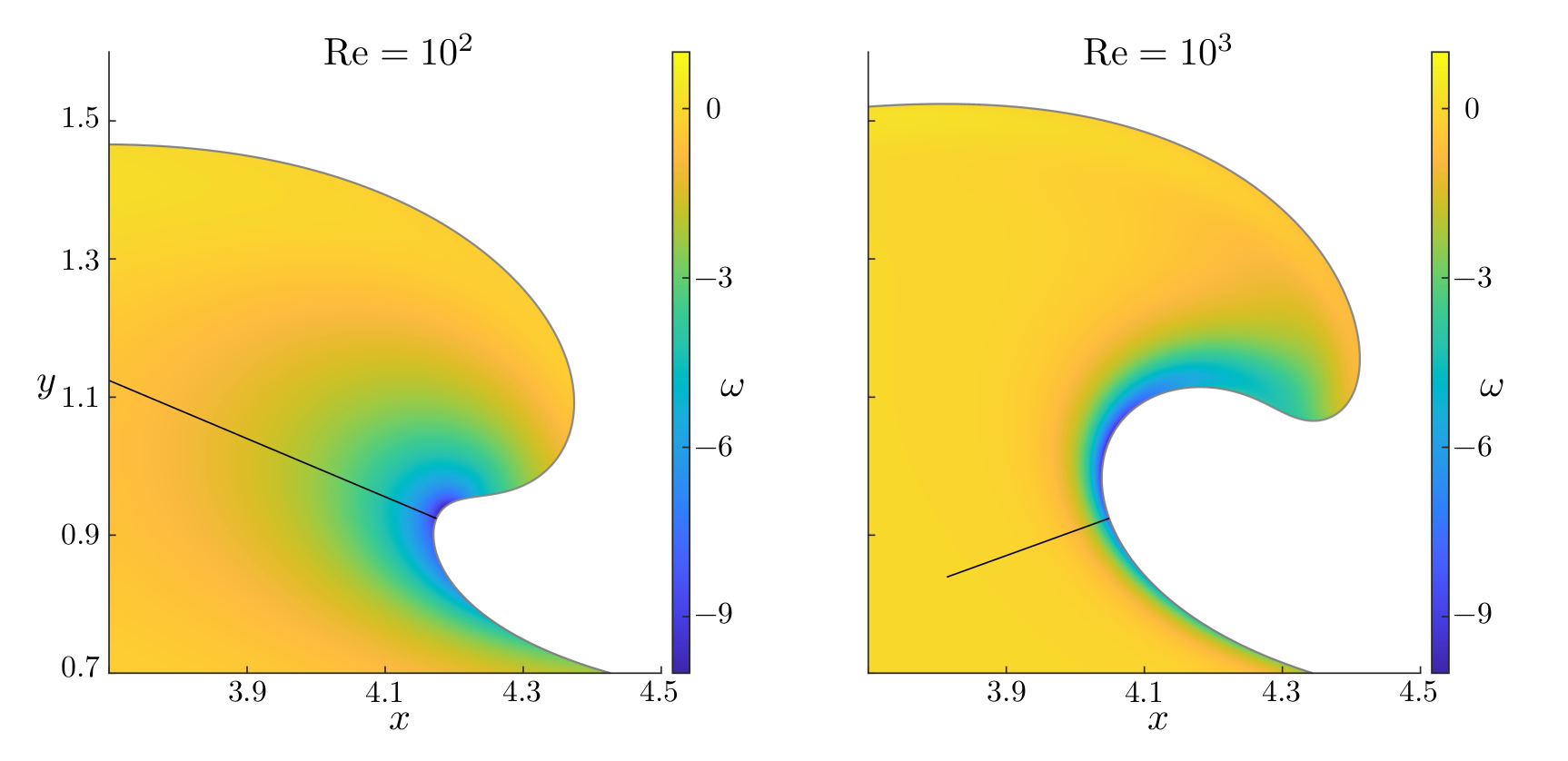

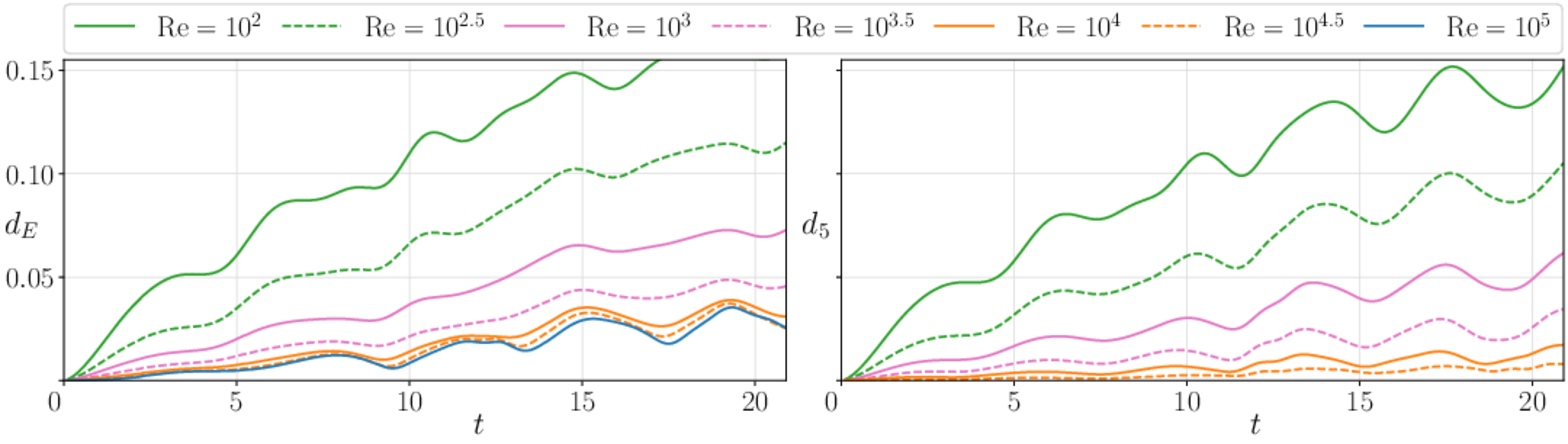

Figures (from R. & Dormy (2024)) - Convergence to the inviscid solution (computed using the numerical method of Dormy & Lacave (2024) )

A local equation for the kinetic energy can be obtained directly from the Navier-Stokes system, \[ \frac{\mathrm{D}}{\mathrm{D}t} \left( \frac{\boldsymbol{u}^2}{2} \right) = \boldsymbol{u} \cdot \boldsymbol{g} - \boldsymbol{u}\cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} p \style{color: #42affa;}{\ - \frac{1}{\mathrm{Re}}\, \Big[ \boldsymbol{\nabla}\cdot \big( \boldsymbol{u}^{\perp} \omega \big) + \omega^2 \Big]} \] with \( \boldsymbol{u}^{\perp} = [-u_y, u_x] \). The dissipation arises in the support of the vorticity \(\omega\).

Generation of vorticity can be understood in light of the stress-free boundary condition, \[ \begin{align} p \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} - \frac{1}{\mathrm{Re}} \, \Big[ \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u} + \big(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u}\big)^{\top} \Big]\, \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} = 0 \qquad & \Longrightarrow \qquad \hat{\boldsymbol{\tau}} \, \Big[ \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u} + \big(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u}\big)^{\top} \Big]\, \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} = 0 \\ & \Longrightarrow \qquad \omega = 2 \kappa \big( \boldsymbol{u} \cdot \hat{\boldsymbol{\tau}} \big) - 2 \partial_s \big( \boldsymbol{u} \cdot \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} \big) \end{align} \]

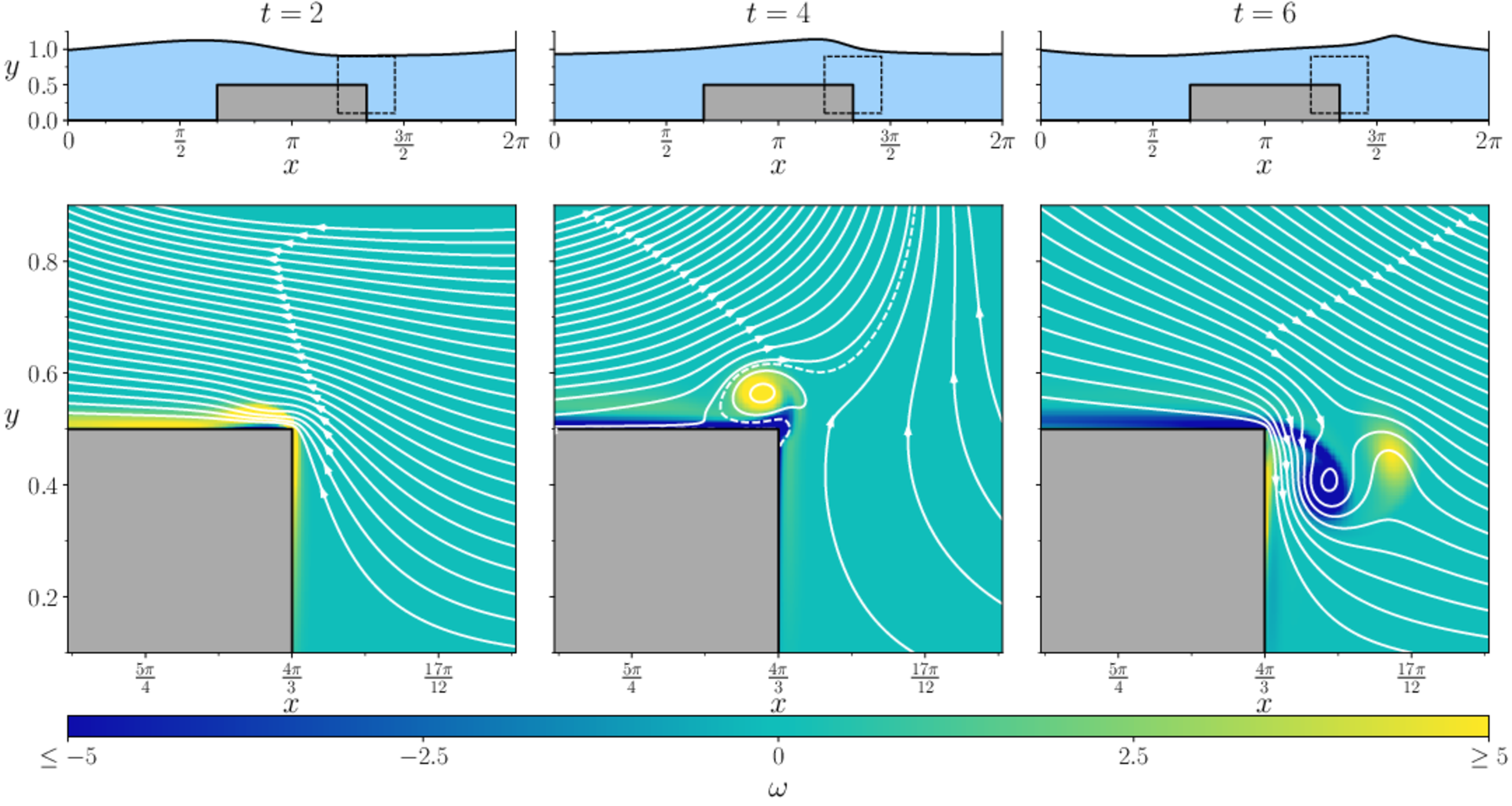

Figures (from R. & Dormy (2024)) - The vorticity generated during the \(\mathrm{Re} = 10^3\) simulation.

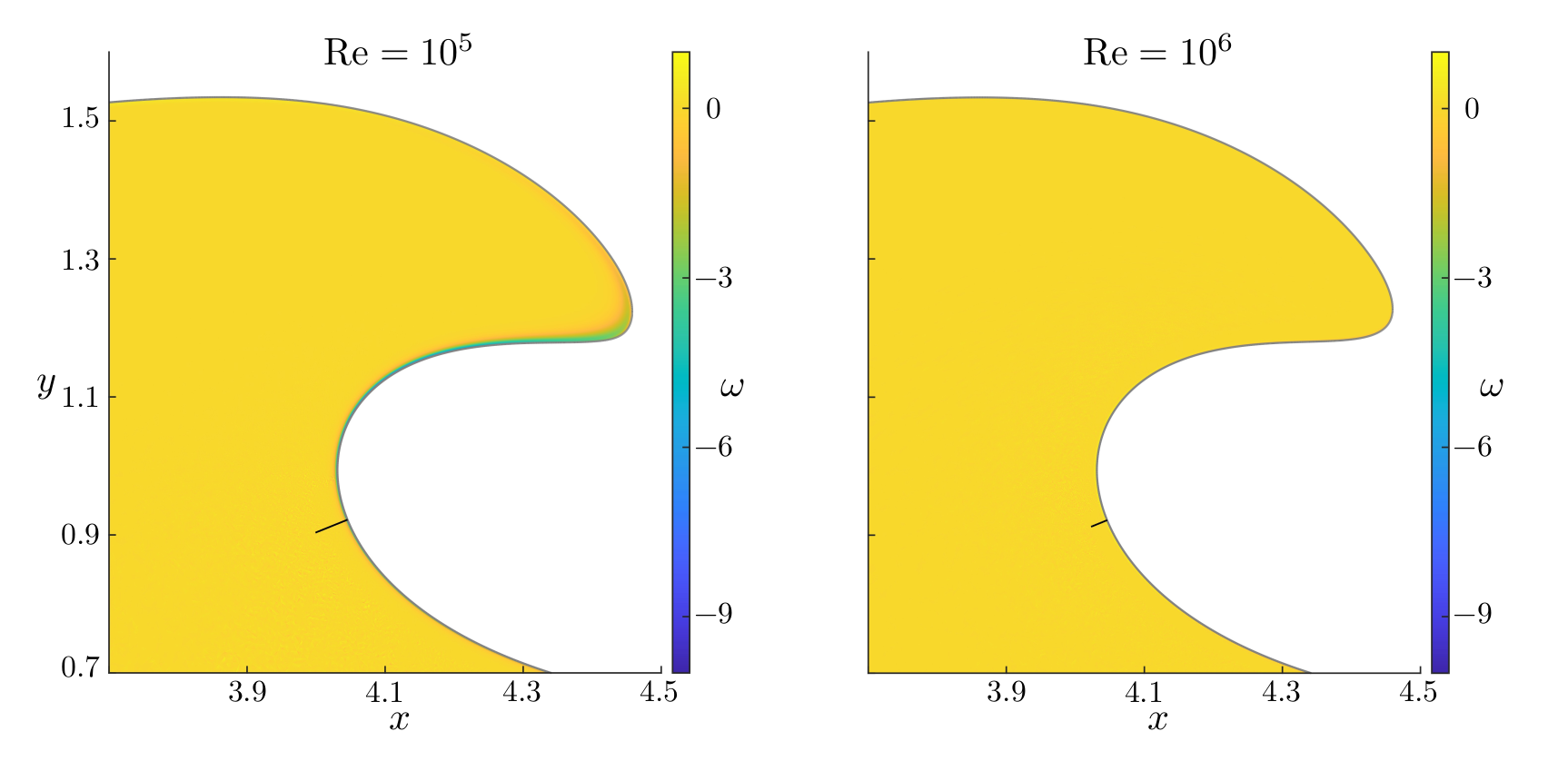

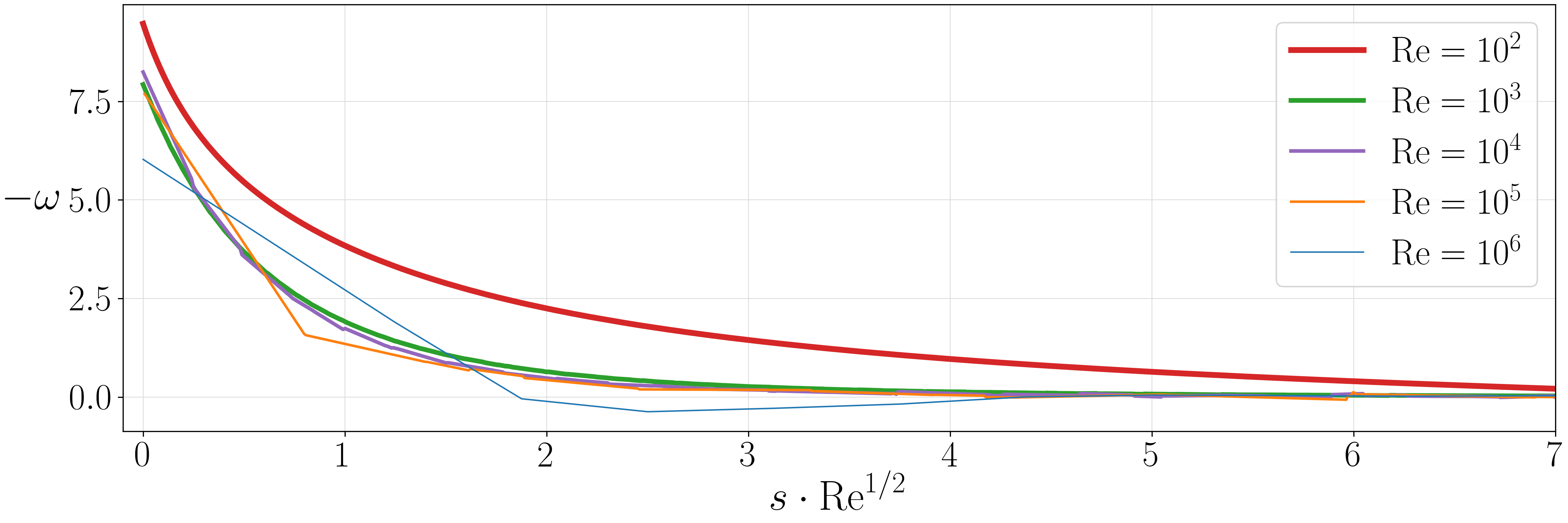

Figures (from R. & Dormy (2024)) - Close-up on the Boundary Layer at time \(t = 2.9\)

Figure (from R. & Dormy (2024)) - Corresponding vorticity cross section.

Stress-free boundary condition on the free surface \[ \begin{align} p \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} - \frac{1}{\mathrm{Re}} \, \Big[ \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u} + \big(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u}\big)^{\top} \Big] \, \hat{\boldsymbol{n}} &= 0 && \text{on } \Gamma_i(t) \end{align} \] Navier No-slip/Dirichlet boundary condition on the bottom topography \(\Gamma_b\), \[ \boldsymbol{u} = 0\qquad\text{on } \Gamma_b \]

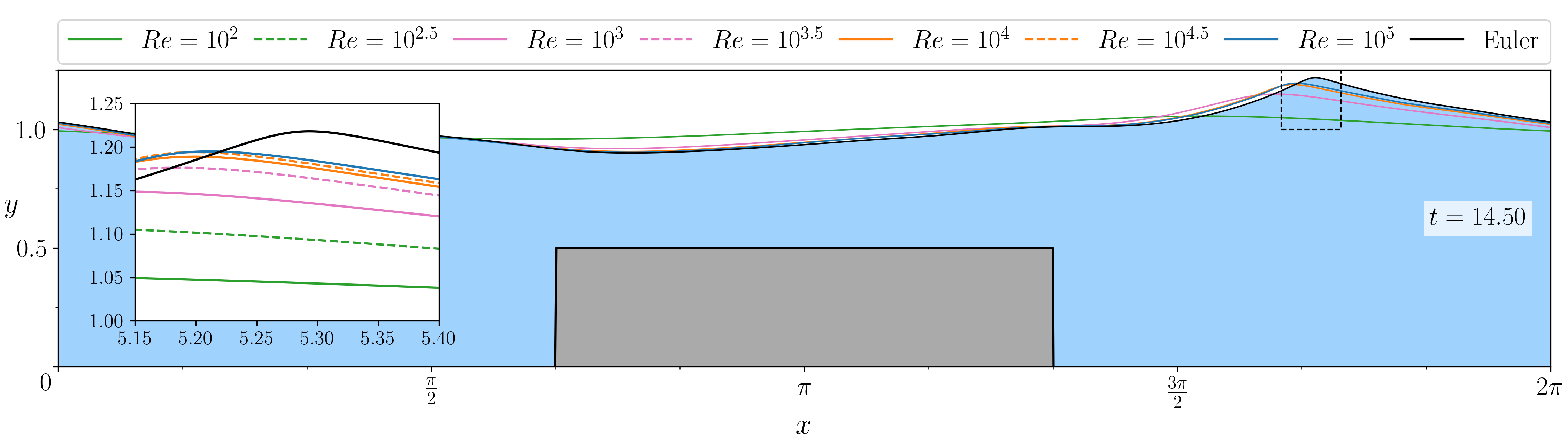

Figure (from R. & Dormy (2025, submitted)) - Comparison of the free surfaces in the case of a water wave propagating over a sharp rectangular step, for different values of Reynolds' number \(\mathrm{Re}\). The "Euler" result has been computed using the numerical method of Dormy & Lacave (2024).

We now use the no-slip/Dirichlet boundary conditions \( \boldsymbol{u} = 0 \) on \(\Gamma_b\)

Animated Figure (from R. & Dormy (2025, submitted)) - Interface evolution for a Reynolds number \(\mathrm{Re} = 10^5\), with a non-breaking water wave propagating over a sharp rectangular step.

Phenomenon already observed by Lin & Huang (2010)

We now use the no-slip/Dirichlet boundary conditions \( \boldsymbol{u} = 0 \) on \(\Gamma_b\)

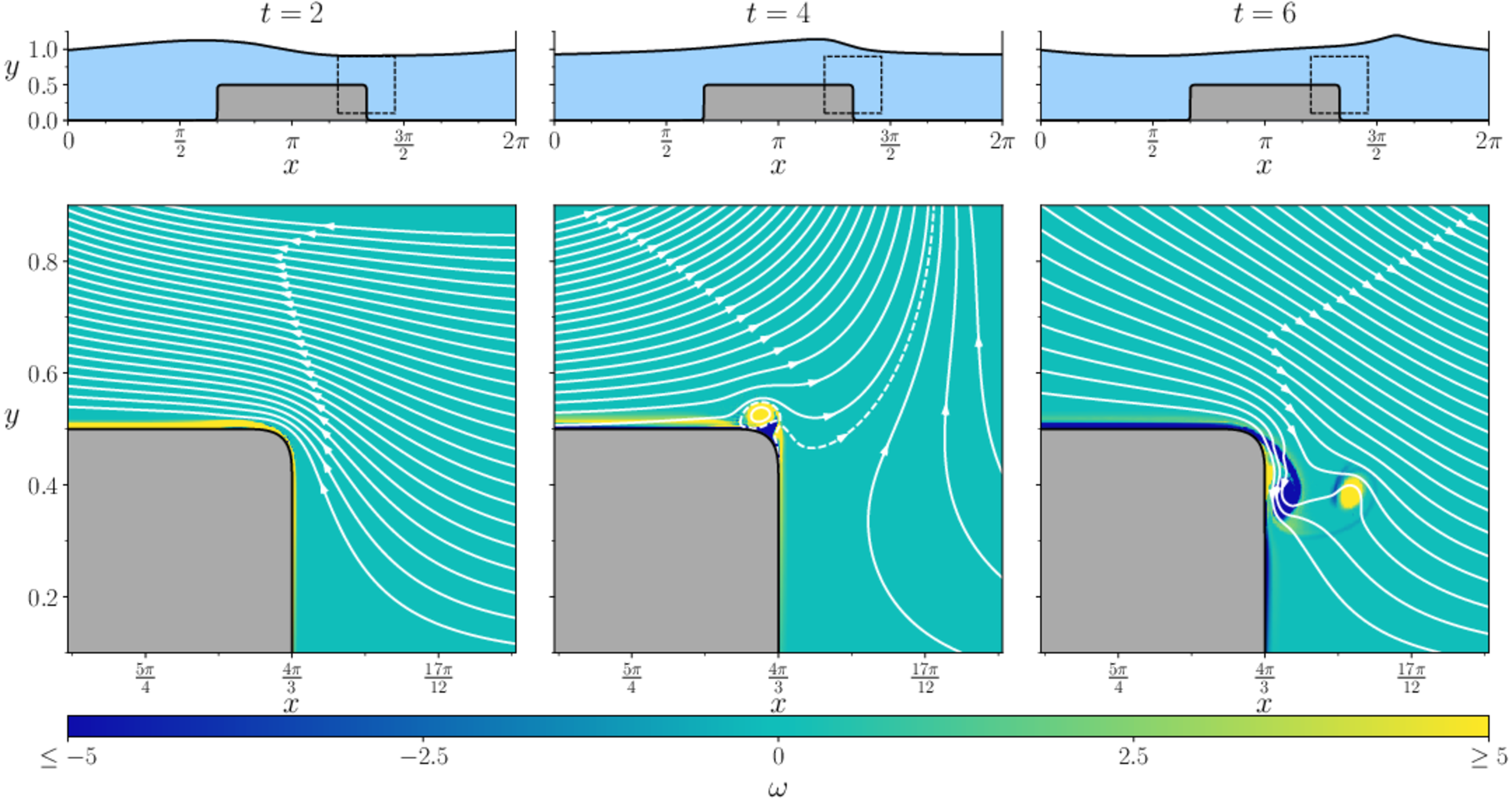

Animated Figure (from R. & Dormy (2025, submitted)) - Interface evolution for a Reynolds number \(\mathrm{Re} = 10^5\), with a non-breaking water wave propagating over a smoothed/mollified rectangular step.

When can we expect a convergence of the viscous solution to the inviscid (irrotational) one as \(\mathrm{Re}\to + \infty\)?

-

Without bottom topography:

⤷Masmoudi & Rousset (2017) (with small amplitude assumption)

⤷A similar result should hold up to the splash singularity -

Topography \(\Gamma_b\) on which the Navier boundary condition is enforced:

⤷Evidences that it should work over a flat topography (up to the splash singularity)

⤷Non-flat topographies \(\to\) not tested yet! -

Topography \(\Gamma_b\) on which the no-slip/Dirichlet boundary condition is enforced:

⤷Evidences that it should not work over non-flat topographies, the boundary layer might separate.

⤷Should the topography be flat, we cannot conclude...

Merci de votre attention!

Proposition

At a time \(t \geq 0\), if the solution to the BW eqs. has not broken, then the couple \((h,\Psi)\) is a (formal) solution of the Water Waves equations.

How to obtain this result?

- The evolution equation for \(\partial_t \gamma_x\) yields a useful formula for \( \partial_t X_t^{-1} \)

- Compute both \( \partial_t h \) and \( \partial_t \Psi \) readilly

Simpler case: Burgers' equation \[\partial_t u + u \partial_x u = 0\]

Consider Burgers' equation's associated characteristics eqs. (which can break), \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rcl} \partial_t \gamma_x &=& \gamma_z \\ \partial_t \gamma_z &=& 0 \end{array} \right. \]

Define \( X_t(s) = \gamma_x(t,s) \) and \( u(t,x) = \gamma_z\big(t, X_t^{-1}(x)\big) \). The evolution of \(\gamma_x\) yields an formula for \( X_t^{-1} \), \[ \begin{align} 0 \style{color: #42affa;}{\ = \partial_t x} &= \partial_t \big[ X_t \circ X_t^{-1} \big] \\ &= \partial_t \Big( \gamma_x\big(t,X_t^{-1}(x)\big) \Big) = \partial_t \gamma_z + \partial_t X_t^{-1}\ \partial_s \gamma_x \end{align} \]

Finally, there remains to put everything together \[ \begin{align} \partial_t u(t,x) &= \partial_t \Big[ \gamma_z\big( t, X_t^{-1}(x) \big) \Big] = \partial_z \gamma_z + \partial_t X^{-1}_t \ \partial_s \gamma_z = -u \cfrac{\partial_s\gamma_z}{\partial_s \gamma_x} = -u \partial_x u \end{align} \]

We define the function space \[ \mathbf{H}^1_{\Gamma_b}\big(\Omega(t)\big) = \Big\{ \boldsymbol{v} \in H^1 \big( \Omega(t) ; \mathbb{R}^2 \big) : \boldsymbol{v} \cdot \hat{\boldsymbol{v}} = 0 \text{ on } \Gamma_b \Big\} \] without assuming the incompressibility directly in the function space!

Find \( \boldsymbol{u} \in C^1\big([0,T) ; \mathbf{H}^1_{\Gamma_b}\big) \) and \( p \in L^{\infty} \big([0,T) ; L^2\big) \) such that, \[ \int_{\Omega(t)} \boldsymbol{v} \cdot \partial_t \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{v} \cdot \big( \boldsymbol{u} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u} \big) + \frac{2}{\mathrm{Re}}\, \mathsf{S}(\boldsymbol{v}):\mathsf{S}(\boldsymbol{u}) - p \boldsymbol{\nabla}\cdot\boldsymbol{v} + q \boldsymbol{\nabla}\cdot\boldsymbol{u} - \boldsymbol{v} \cdot \boldsymbol{g} = 0 \] for all \( \boldsymbol{v}\in \mathbf{H}^1_{\Gamma_b}\big(\Omega(t)\big) \), \(q\in L^2\big(\Omega(t)\big)\) and at all time \(t\in(0,T)\).

Let us consider the Poisson equation, \[-\Delta \psi = \omega\qquad\text{in }\Omega \subset \mathbb{R}^2\]

The Boundary Integral/Element Method

\(\psi\) is extended by \(0\) in \(\mathbb{R}^2-\Omega\), leading to the following representation formula, \[ \begin{align} \psi(\boldsymbol{x}) =& \int_\Omega \omega(\boldsymbol{y}) G(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{y})\, \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \\ &+ \int_{\partial\Omega} \partial_n \psi(\boldsymbol{y}) G(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{y})\, \mathrm{d}S(\boldsymbol{y})\\ &+ \int_{\partial\Omega} \psi(\boldsymbol{y}) \partial_n G(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{y})\, \mathrm{d}S(\boldsymbol{y}) \end{align}\]

The Dipole Method

\(\psi\) is extended continuously in \(\mathbb{R}^2-\Omega\), leading to the following representation formula, \[ \begin{align} \psi(\boldsymbol{x}) =& \int_\Omega \omega(\boldsymbol{y}) G(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{y})\, \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \\ &+ \int_{\partial\Omega} \gamma(\boldsymbol{y}) G(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{y})\, \mathrm{d}S(\boldsymbol{y}) \end{align}\]